| AVAILABLE

Gonzalvo Carelli

(Neaples 1819 – 1900)

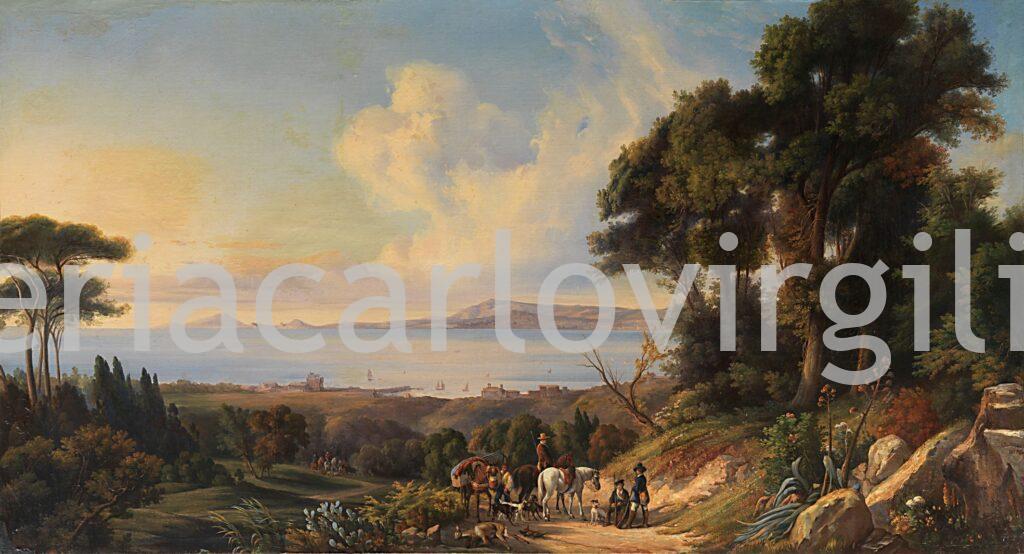

VIew of the Gulf of Naples from the Royal Gardens of Portici • 1846

oil on canvas, 108 x 198 cm

Signed, right front on rock: “Gonzalvo / Napoli”; on the back, painted on the lining: “Gonzalvo Carelli / Napoli 1841”

The view is painted from the eastern part of the gulf, on the nether slopes of Vesuvius. Portrayed in the lower part is uneven terrain, with protruding rocks, cut through with small valleys and declivities as the land drops towards the sea. The vegetation is typical of the Vesuvian zone, scrub dominated by pines and oaks, dotted with the occasional prickly pear and agave, with clearings that, beyond the lower line of trees, push on to the sea. Near the oak forest enclosing the composition on the right are four huntsmen – one on horseback – with four dogs, a donkey laden with hunting equipment and two more horses. A fawn and three pheasants lie on the ground. From the left, on the path, two more huntsmen on horseback with dogs and two assistants are approaching. Along the coast, or rather, on the ridge overlooking the sea, almost in the centre we see a square tower and pier beneath, and looking to the right, a convent and two groups of houses. The gulf of Naples, dotted with sailing boats, is defined by the coastal arc of the city of Naples, overlooked by the hill of Vomero with Castel S. Elmo and Certosa di S. Martino, and concluded with the point of Pizzofalcone to which the Castel dell’Ovo bridge is attached. Behind is the high Camaldoli hill, beyond which you can see the hills of the Campi Flegrei stretching out to sea to the elevation of Capo Miseno, followed by the islands of Procida and Ischia enclosing the gulf’s expanse.

The veduta described corresponds to the view from Portici, although some topographical elements are a little changed to suit the demands of portrayal. The foreground also matches the further end of Portici, towards Resina (now Herculaneum), known today, as in the eighteenth century, with the toponym Granatello, due to the presence in the olden days of a large number of pomegranate trees. The woody area where the figures have been hunting seems to have been in the lower wood of the royal park of the Palace of Portici, where the kings of Naples hunted animals of feather and fur, reared in a pheasantry and enclosures. A hypothesis supported by the presence of a fawn and three pheasants. Various other aspects confirm the identification of the place, and some elements, although modified, still occupy the same position and carry out the same functions as those present in the painting. For example, clearly evident is the pier at the port, still active, commissioned by Ferdinand IV in 1774, and on the right the eighteenth century Convent of S. Pasquale, whose modern façade still dominates the coast of Granatello. Whereas the Fort of Granatello, whose square tower is sticking out to the left of the pier, no longer exists, having been demolished in 1873. It was erected in the sixteenth century on the Capo del Fico to defend the territory then further fortified with a ravelin in 1738-40 (Formicola 2011, p. 25, passim). It caught the attention of vedutisti such as Lusieri and Della Gatta, also appearing in some prints. Another prestigious building, the eighteenth century Villa d’Elboef, now in very poor condition, seems to me to be visible to the right of S. Pasquale, closer to the sea. When Carelli painted the view, the topography was rougher than it is today and there was a greater difference in height between the sea and the plateau formed from Vesuvian lava that hid the railway, which from 1839 almost reached the port and follows the same route today.

This painting was part of a series commissioned by Tsar Nicholas I from Carelli and other Neapolitan artists. Between 1845 and 1846, the sovereign made a long diplomatic tour of various Italian and European capitals. As far as Palermo he was accompanied by the Tsarina, who for reasons of health, needed to spend time in milder climates. The imperial family and court reached Sicily on 23 October 1845, remaining there until the following March, while on 5 December, the Tsar travelled on to Naples to take up his diplomatic tour again (Lefevre 1959, III, pp. 417-433; Palermo 2007). In less than a week at the Bourbon capital, he managed to participate in a couple of parades and visit several military establishments, the symbolic cultural spots such as Pompeii and the National Archaeological Museum, and modern industrial Naples, such as the locomotive factory, the Opificio di Pietrarsa, and the naval dockyards at Castellammare, as well as the royal palaces at Portici and Caserta, castles and monuments, such as Certosa di S. Martino (Del Pozzo 1857, pp. 507-508). Despite such frenetic activity, he also managed to get an idea of the Neapolitan artistic production of the time, however, it is hard to say, given the available time, whether he visited ateliers, as he did on the Roman sojourn, or whether it was by means of a small exhibition arranged for him at the Royal Palace of Naples, where he was staying as a guest (Karčeva in Palermo 2007, p. 15), or perhaps by following pointers from someone like Ambassador Potocki who was in contact with many local painters. The Tsar’s purchases were for the most part of landscape painting, targeting the best and most noted artists of the genre: Smargiassi, Vervloet, Carelli and Giacinto Gigante (Karčeva in Palermo 2007, pp. 15-16). This last, thanks to the good offices of Potocki, carried out two large paintings for the Tsar and was sent to the Tsarina in Sicily to make paintings of certain landscapes on the island (Ortolani 1970, pp. 208- 209).

The youngest of the landscapists contacted by the Tsar was Gonzalvo Carelli, born in 1818 but already well established: he had trained with his father Raffaele and improved his watercolour technique with William Leicht, and by the 1830s he had received his first plaudits at Bourbon exhibitions, so much so that at the 1837 exhibition the king brought two of his views. From the start, Carelli could count on exalted patrons, among others the Duke of Terranova, who in 1837 awarded him a bursary to go to Rome, where he remained until 1840, frequenting the artists from the French Academy in particular. After a brief return to Naples, in 1841 he left for Paris, where he stayed three years, developing his technical knowledge and his relationships with various French landscape artists (Martorelli 2002, pp. 15-16), exhibiting at the Salons and enjoying the patronage of the court of Louis Philippe.

By 1845 Carelli, thanks to his ample experiences, had reached artistic maturity and could count on high placed support and buyers, from the courts of Naples and France, to English lords and Neapolitan aristocrats (Napier 1855. Ed. cons. 1956, pp. 86-88; Martorelli 1991, II, p. 740). Excellent reasons to include him in the list of maestros fit to work for the Tsar. A source that seemed to know him well, Lord Napier, recalls that once he returned from Paris, he took part “in the Russian Emperor’s patronage, for whom he made a veduta of Naples from the Park of Portici and a fine panorama from the Convent of the Camaldoli” (Napier 1855. Ed. cons. 1956, p. 88). We can’t tell whether these are the two paintings by Carelli listed in the Neapolitan archives, indeed the only two views he carried out for the Tsar, which were exported in March 1847 and March 1849, are not described (AS-MANN, CABBAA, XX B 1-4.14 e IX D 3-2.11). However, we are certain that he sent at least five paintings to Russia, three of which were delivered to Tsarina Alexandra (РГИА [Russian State Historical Archive], ф. 1338, оп. 4, д. 37, ff. 17/18). Among these, the “View of the Gulf of Naples from the Royal Garden of Portici” should be the painting in question here, and the work inventoried in 1856 as n° 367 among the assets of the deceased Nicholas I, as “View of the Gulf of Naples, 28½ by 48.” This work, sharing inventory number and measurements, was catalogued around 1894 by Baron Lieven and described as “Gonsalvo Carelli, View of the Gulf of Naples with Huntsmen, 1846, 29 by 47⅝” (Архив ГЭ [Hermitage Archive], ф. 1, оп. 6, лит. А. Дело 42-А, л. 50). Baron Lieven is clearly describing our painting, adding the date 1846.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the veduta was located in a drawing room at the Winter Palace, St. Petersburg, as shown in documents and a watercolour by Eduard Heu, portraying the interior of a room at the imperial residence (1872; St. Petersburg, Hermitage Museum, inv. n° OP-14419): reproduced, hung to the sides of a fireplace with mirror, the View of the Gulf of Naples from the Terrace of the Royal Palace, by Smargiassi (see entry….Smargiassi), and this View of the Gulf of Naples from the Royal Gardens of Portici, by Carelli. After the fall of the monarchy, the canvas was moved to the Hermitage depository and in 1928, declared of little historical interest and sold.

View from Portici was signed by Carelli only as Gonzalvo, while on the back there is an inscription with both forename and surname and the date 1841, contrasting with the date of 1846 noted down by Lieven. It seems that the work underwent restoration in the early twentieth century. On the occasion it was re-lined, and on the new canvas, now hard to remove, the author’s details and the date would have been re-written, so there may have been an error in copying, the six being substituted by a one. My opinion is that the correct date is 1846 and that the baron obtained it from the original inscription on the back of the first canvas. Moreover, there is no evidence that Nicholas I commissioned works before 1845, even from artists more famous than Carelli.

Some of the Tsar’s Neapolitan experiences are fundamental to understanding the iconographic novelties of one of the paintings requested of Smargiassi (see entry…. Smargiassi). It is also possible that the choice of point of view of this veduta by Carelli, not entirely new, was motivated by a visit to the Royal Palace at Portici made by the sovereign on 11 December 1845 (Giornale del Regno 12 December 1845, p. 1088). In this work the artist shows his ability to compose large surfaces and to meet the taste of the most courtly and sophisticated clientele. In such a case he cannot put across a reality pervaded by emotions, according to the best dictates of Pitloo and the Posillipo painters, but has to create a fine composition, with the natural elements disposed in a scenographic manner, not necessarily following their true disposition. A work carried out in the studio, with the help of notes taken from life: so the oaks and pines are located at the sides as scenic wings, the rock and agave are typical elements from Gonzalvo’s repertoire, and even the portrayal of the arch of the gulf is somewhat forced in order to bring out certain points. Animating the scenery are animals and huntsmen, well rendered as always with Carelli. Paintings of this genre are typical of those years and convey the classical taste, inspired by Claude or Poussin, developed through knowledge of the French landscape artists.

Renato Ruotolo

For further information, to buy or sell works by Carelli Consalvo (Gonsalvo) (1818-1900) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650