| NOT AVAILABLE

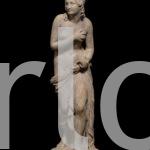

Giuseppe Sanmartino,

attributed to (Naples 1720 – 1793)

Couple of Figures in Chinoiserie: Female Figure at the Mirror, Male Figure with Mirror and Mask

1770 ca.

Marble, gildings, height 80 cm

Provenance: San Giorgio a Cremano, Naples, Villa Bruno; Rome, Bruno family

These unique marble statuettes – of two people whose features, hairstyle and dress can be linked to what was once known as the Celestial Empire, fall into the category of Chinoiserie. Both are wearing clothes that are bordered in gold leaf; the woman is inclining her head as if to look into the mirror held by the man, who in his other hand holds a mask, also golden. But these are not works of generic imitation of the Orient, vaguely undefined geographically, belonging to a period in which few people could distinguish what was Chinese, Indian or Turkish. Their very particular craftsmanship reveals the predominance of the personality of an artist who ‘interprets’ in his own way a simple iconographic reference taken from a print or painted cloth.

To narrow the focus: when in 1992 Elio Catello gathered together all the information on the diffusion of Chinoiserie and Turquerie in Naples available to date – since in practice up to the nineteen seventies research was concentrated on the most famous and prestigious piece, Maria Amalia of Saxony’s porcelain salon, made for the Palace of Portici and now at Capodimonte; and on the Bourbon villas at Herculaneum and Palermo, although they were considered an extremely late manifestation of this taste – it was noticed that in the vice regal and then Bourbon capital, the phenomenon was also considerable, although for a long time – including most of the seventeenth century and the first part of the eighteenth – there were practically no identifiable artefacts. Although outside the routes of the various companies belonging to the British, Dutch and French Indies, the port of Naples was connected to those nations’ main seaports, as well as, obviously, those of the Spanish, through a dense network of commerce and ships’ passages, run by local and ‘foreign’ merchants that had only recently begun to be set up. In this way by the end of the sixteen thirties the presence of oriental objects spread to Naples and in another forty years they were constantly to be found in inventories belonging to merchants and the rich bourgeoisie, to then appear in the aristocratic collections, becoming a genuine fashion by the end of the century. Nonetheless it would be Charles de Bourbon’s enthronement in 1734, the start of diplomatic relations with the ‘Sublime Porte’ in 1741 and the opening of the Royal Porcelain Factory at Capodimonte in 1743 that would increase the production of ‘oriental’ objects; also to be found in religious environments.

Despite often being considered ‘dated’, in the sense of being excessively positivist and lacking global criteria, the method of the art historian Giovanni Morelli (1816-91) – who put forward scrutiny of details (ears, hands, draping of clothes etc) as the manner to differentiate the hand of the artist from those of imitators – remains a point of reference, above all for sculptures, in that they are sometimes more difficult to decipher than a painting.

And in this case it turns out to be useful because it is the details that lead us to the author of these works: if a comparison is made between the details of the female figure’s hands and those of Allegory of Charity (1757-58, Naples, Chiesa della Certosa di San Martino), or to those of the Angel Holding Torch (c. 1756-58, Naples, Chiesa di Santa Maria di Caravaggio),

or indeed those from the later Allegory of Abundance (1770-71, Martina Franca [Taranto], Collegiata di San Martino), a full identity of the design concept and modelling is easily apparent. The soft, tapering fingers are bent, and sometimes cross over with the same coquettish grace that all their owners have in common, whether they are angelic, allegorical or holy figures. Other obvious comparisons can be made when examining the quality of the modelling in the angle of the head, again in the female figure, with faces of the Cherubs that support and crown the tabernacle in the Chiesa della Nunziatella (1757-58), once a Jesuit institution; or with the head of the Angel Holding Torch (Maddaloni [Caserta], Chiesa di San Francesco). All the works in these comparisons are attributed to the main Neapolitan sculptor and among the principal sculptors in Italy of the century: Giuseppe Sanmartino (1720-1793). Creator of extraordinary technical virtuosity, in the true sense of the term: surpassing reality, the sculptor has been the object of numerous monographs (see the bibliography attached to the study by Elio Catello of 2004), although at the moment an annotated catalogue on his production does not exist that also includes the most Neapolitan of the ‘genres’: the nativity scene. Although many works are attributed to him in this field, they often err on the side of ‘amateur’ assignment, and only some of them can really be said to be by his hand, distancing themselves from imitations for the very high quality of the modelling and chromatic finishes; and nonetheless not always easily located in Sanmartino’s long period of activity if not, when possible and using a wide spread, comparing them with the works in marble.

In the sculptures under discussion comparisons can also be made with Sanmartino’s works of this type: if we look at some of the features of the Figure of a Woman such as the nose or the parted lips, or the way the hair is gathered behind the head as though it were modelled in wax rather than sculpted, taking two from many possible examples, we can liken them to the Young Woman (Naples, Museo Nazionale di San Martino), or to the Angel (private collection), both works of solid authenticity, and that seem to me to support the attribution to the sculptor. The same argument applies for the comparison between the features of the Figure of a Man and those of the Herder (private collection), a work well known to research; where some apparently secondary details, like the curve of the chin, are completely analogous.

Here too, previous considerations hold and changing gender of protagonist the modalities of design change as do the rendering of the hands: for instance we find in Figure of a Man the same fingers made as though the phalanxes were a series of parallelepipeds, as can be seen – again one of many examples – on the hand of Saint Paul (1760, Naples, Chiesa di San Giuseppe dei Ruffo). In these statuettes – furthermore made in a format that was very unusual in Neapolitan sculpture in the eighteenth century – the drapery is simplified with respect to the usual dress seen on Sanmartino’s sculptures, but their apparently synthetic rendering – there is a difference between that of the woman and the man, as if in the former the sculptor wanted to ‘take advantage’ of being able to use the shawl as a flourish – should, I think, be linked to the subject and the format. While the semi-lucid patina, which I believe to be original, is perhaps in imitation of ivory. A further consideration is the hypothesis of the original recipient of the statuettes. Current research is endeavouring to establish this, bearing in mind the importance of the artist, defined in 1775 as «the primary sculptor of this Capital», narrowing the field to some specific places – the Bourbon residences of Herculaneum and Portici, where Chinese decorated spaces still abound – and checking old inventories for the presence or lack of objects referable to these. Not to leave out another feasible theory regarding a location, the premises of one of the most rigidly ascetic orders, where the presence of ‘fashionable’ ornaments would be entirely unexpected. Namely the Monastery of San Martino, where there are still two rooms, once the prior’s quarters, whose ceilings are richly decorated with Chinoiserie and Turquerie and that it appears were being furnished with the purchase of porcelain objects, precisely in the years in which Sanmartino was working in their church (1757-58).

Gian Giotto Borrelli

Bibliography

Elio Catello, Cineserie e turcherie nel ’700 napoletano, Sergio Civita Editore, Napoli 1992.

Elio Catello, Giuseppe Sanmartino, 1720-1793, Electa Napoli, Napoli 2004.

Bibliography

J. Hall, Dizionario dei soggetti e dei simboli nell’arte, Longanesi & C., Milano 1983.

G. Mendola, Nuovi documenti per Van Dyck e Gerardi a Palermo, in 1570. Porto di mare. 1670. Pittori e Pittura a Palermo tra memoria e recupero, catalogo della mostra (Palermo, 30 maggio-31 ottobre 1999), a cura di V. Abbate, Electa Napoli, Napoli 1999, pp. 88-105.

X. Salomon, Van Dyck in Sicily: 1624-1625 painting and the Plague, catalogo della mostra (Dulwich Picture Gallery-London, 15 febbraio-27 maggio 2012), Silvana editorial, Cinisello Balsamo, Milano 2012.

B. De Dominici, Vite de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti napoletani, III [1742], ed. cons. a cura di F. Sricchia Santoro e A. Zezza, Paparo Edizioni, Napoli 2008, III, pp. 1182-1183.

Katharina Dohm, Claire Garnier, Laurent Le Bon, Florence Ostende (a cura di), Dioramas, catalogo della mostra, Palais de Tokyo, Parigi, 14 giugno – 15 settembre 2017, ill. p. 22.

The Carlo Virgilio & C. Gallery searches for works by Sanmartino Giuseppe (1720-1793)

To buy or sell works by Sanmartino Giuseppe (1720-1793) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650