| AVAILABLE

Gabriele Smargiassi

(Vasto (CH) 1798 – Napoli 1882)

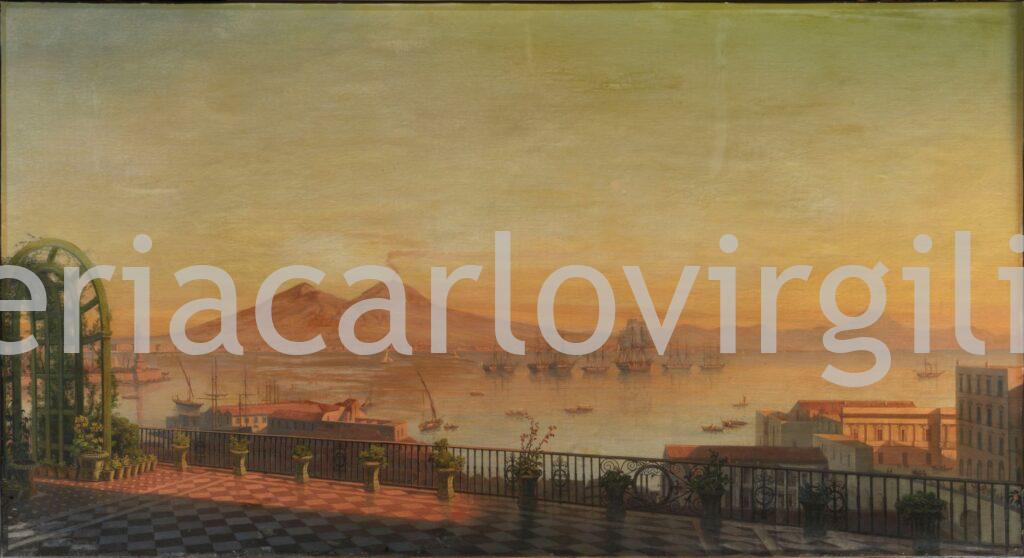

Veduta del Golfo di Napoli presa dalla terrazza del Real Palazzo • 1846

Oil on canvas, 105.5 x 196 cm

The view, immersed in the afternoon light, is from the terrace running along the left side of the Royal Palace of Naples, linking the first floor state apartments to those for entertaining and now occupied by the National Library. The cast iron railing cuts an oblique line across the whole painting, dotted at regular intervals with plants in terracotta vases; other vases in different shapes are sitting at the foot of the wooden arch of the grillage. To the right of the terrace, below, is the lower end of Salita del Gigante, now via Cesario Console, coming from Largo di Palazzo. Foundation arches can be seen on the side of the sea, and on the right is the flank of the Admiralty building on the corner of via S. Lucia; the end of the Salita is enclosed by a military quarter, occupied in the early eighteen hundreds by the infantry, with the façade on one level, accented by pilasters and ionic columns, replaced around 1935 by a building also pertinent to the Marines (Ferraro 2010, p. 143). The height of the terrace means not all the industrial buildings below are visible: only a few roof trusses in the dockyard and buildings around the harbour, from which you can see the first stretch of the access channel from the sea but not the body of water where the presence of two ships at anchor is indicated by the tops of their masts emerging from among the buildings. The dockyard disappeared at the end of the 1920s, substituted by the Giardini del Molosiglio and via Acton; the harbour, now known as Darsena Acton, has the same perimeter as the Bourbon version and also, in part modified, a pair of the buildings visible in the painting. On the left, demarcating the military port, the large wharf emerges, ending in the so-called “Wharf Lantern,” a lighthouse of fifteenth century origins and the hallmark of many Neapolitan views from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, demolished in 1932. The gulf is enclosed at the far end by the bulk of a smoking Vesuvius, extending on the right until it merges with the Monti Lattari chain, dominated by Mount Faito and girding the sea to close the gulf and form the Sorrentine peninsula. The presence of the grillage, and the viewpoint, exclude the city’s sea front from the picture but not the stretch of coast that, just beyond River Sebeto, unfolds at the foot of Vesuvius. While from the left, we can make out the final extremities of Naples, which is to say the long building of the Granili, divided into four continuous bodies. Following on from there are the coastal houses and villas of San Giovanni a Teduccio, Barra, Portici, Resina (now Herculaneum), and Torre del Greco, with their farmhouses climbing up the slopes of the volcano. In the stretch of sea next to the royal terrace, among sailing boats and recreational vessels, six frigates are at anchor, two sail and steam and four sail, bearing the Russian flag.

The work, neither signed nor dated, has always been held to be by Gabriele Smargiassi and linked to a commission from Nicholas I of Russia, a great connoisseur and acquirer of works of art, often destined for the Hermitage Museum (Palermo 2007). Sources and documents allow us to date the work to 1846, to confirm the attribution and include it in those ordered by the Tsar during his sojourn in Naples (6-12 December 1845). The presence of the canvas in the third private apartment of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg is confirmed in 1872 by a watercolour by Eduard Hau (1807-87), conserved at the Hermitage Museum (inv. n° OP-14419). The artist captures the interior of a drawing room with exceptional descriptive skill: on the walls, clearly recognisable, our veduta, next to one by Gonzalvo Carelli, also known.

The week Nicholas I spent in Naples was very intense, amidst military parades and visits to symbolic places of culture and modern industry (see listing n°… re Carelli). Nor were meetings with local artists neglected, and perhaps due to the small amount of time at the sovereign’s disposition, these didn’t occur so much at the ateliers as through the filter of a Russian individual who knew the milieu well, such as Ambassador Count Potocki, and thanks to an exhibition, organised at the palace and hence with the consent of the King of Naples, where painters such as Frans Vervloet, Smargiassi and the Carellis exhibited their works. The Russian source supplying this information states that Nicholas I bought a lot of art and commissioned more (Karčeva in Palermo 2007, p. 15). View from the Terrace certainly didn’t belong to the group of paintings bought on that occasion but it was ordered at the time, as was the large (126×214 cm) View of the Neapolitan Coast, still conserved at the Hermitage (inv. 4240), signed by Smargiassi and dated 1847 (Serafini 2021, p. 757, fig. 2).

These two paintings, specifying the patron and original titles, namely View of the Gulf of Naples from the Terrace of the Royal Palace and Mouth of the New Posillipo Road Facing Campi Flegrei, were immediately mentioned in a biography of Smargiassi, revised up to the final months of 1845 (Giucci 1845, p. 458). Here the bibliography of the painting runs out and we move to archival sources’ for mention of the work’s considerable cost, 1,523 ducats, and when it reached Russia, on the ship “Baron Stieglitz”, early in 1847. After being shown to the Tsar at his Peterhoff residence (РГИА [Russian State Historical Archive], f. 1338, op. 4, d. 37, 15 ffv.), the work was hung in a room at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, as can be seen in the painting by Hau. In 1856 it was inventoried among the paintings of the deceased sovereign (n° 366) as “G. Smargiassi, View of the Vesuvius from Naples” while around 1894, listing paintings at the Winter Palace, Baron Lieven makes reference to it with a more generic title, “Smargiassi, View of Naples”, but with the same inventory number (366) allowing us to identify it (Архив ГЭ [Hermitage Archive], ф. 1, оп. 6, лит. А. Дело 42-А, л. 50). After the fall of the monarchy, the canvas ended up in the Hermitage depository and in 1928, declared to have little historical value, was put on the market.

These two cited works might have been the only requests Nicholas I made of Smargiassi, less than those commissioned of Gonzalvo Carelli or Giacinto Gigante, although Smargiassi at the time enjoyed greater prestige, due to his vast international experience, the fact that from 1838 he held the chair of landscape at the Royal Institute of Fine Arts of Naples, and the esteem of the Bourbon court. All in all, an official figure, able to meet the needs of a high level clientele whose tastes he had been familiar with from youth. Indeed, after training with Pitloo, in 1824 he moved to Rome, enjoying the protection of the Duchesse de Saint-Leu, wife of Louis Bonaparte, ex King of Holland, who employed him as painting master for her son, the future Napoleon III, took him to Switzerland in 1828 and then facilitated his entry into the Parisian milieu Smargiassi frequented, with rare trips back to Italy and a trip to London in 1831, until the end of 1837. In Paris he worked for a selective clientele, among whom the Queen of Belgium, and, above all, the court of Louis Philippe, whose children he taught drawing, and Queen Maria Amalia, aunt of Ferdinand II of Naples (Ortolani 1970, pp. 176-184).

Hence, by 1845 the figure of Smargiassi was hard to ignore, by now he had matured a language that took up elements of late eighteenth century vedutism and Nordic tradition as well as Poussin, arriving at a “figurative compromise of atmospheric landscape, of vague Pitloo ascendency, but almost always elaborated in the studio with composed inserts of naturalistic elements, to achieve a final rendering with a scenographic character” (Martorelli in Napoli 1997-98, p. 420). In short, while never betraying the study of nature, the artist had passed the phase more intensely tied to the Posillipo School, painting from life and the lyrical and immediate tone, and was on the point of reaching an elegant composition landscape painting pervaded by romantic and historical accents, and populated by figures from Ariosto and the Bible (For Smargiassi see essays in Naples 1987-88).

In the View from the Terrace Smargiassi gives an eloquent show of his art, creating a very interesting work from an iconographic point of view. Clearly the patron’s request was for him to portray the gulf from the palace terrace, but it might be supposed that it was he who chose the angle at the end, towards the façade. The result is an unusual painting, quite different from coeval works, in that it displays the well-known view of the gulf from a new angle, from the terrace of the roof garden added along the southern side of the palace after the fire of 1837 and completed around 1844. So, for the first time this place assumes the role of protagonist in foreground composition, shown in detail, and given its height with respect to sea level also allowing unprecedented views of the buildings below, from the Arsenal and Darsena, which we intuit more than see when they were and would generally be seen in their entirety: structures and spaces. Moreover, this new point of view brings out another so far neglected aspect, which is to say the military building at the end of Salita del Gigante, towards S. Lucia, which existed for centuries and only now shows itself in its recent neoclassical guise.

So the Royal Palace becomes simultaneously part of the veduta and of its point of view. Being a private place difficult of access, this angle would not have a great following and perhaps only towards 1868 do we see it reappear, with substantial variants, in a painting by Giuseppe Castiglione, for now only known through prints, where Margherita of Savoy, Princess of Piedmont, appears on the terrace with the panorama of the gulf behind her (Porzio 2011, p. 116).

The choice of the terrace as the point of view for the painting was certainly not random, being attributable to the patron’s desire to remember the Neapolitan landscape precisely as he saw it from his rooms. Indeed, we know that during his stay in Naples, Nicholas I was the guest of Ferdinand II of Bourbon in the state apartments at the Royal Palace, which open onto the terrace with the roof garden (Del Pozzo 1857, p. 508). What is more, the painting transmits a marked record of the visit by the presence of the six frigates bearing the Russian flag. They did not belong to the Tsarist fleet but to the Bourbon fleet and recall the welcome extended to the Tsar at his arrival from Palermo: on 6 December, travelling on his steam frigate Bessarabia without a naval escort, he reached Naples and was welcomed at the harbour by King Ferdinand. At that moment, “the crews of the royal ships anchored there saluted, running the Russian flag up their masts,” and when the royal carriages proceeded to the palace, “as they passed, the aforementioned Royal Ships, played the Russian anthem.” Unless the ships’ presence alludes to an exercise that took place on 10 December, but in the harbour and not offshore, involving six Neapolitan frigates in the presence of the King and Tsar (Giornale del Regno 9 December 1845, p. 1075, and 11 December, p. 1081).

Renato Ruotolo

For further information, to buy or sell works by Smargiassi Gabriele (1792-1882) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650