| NOT AVAILABLE

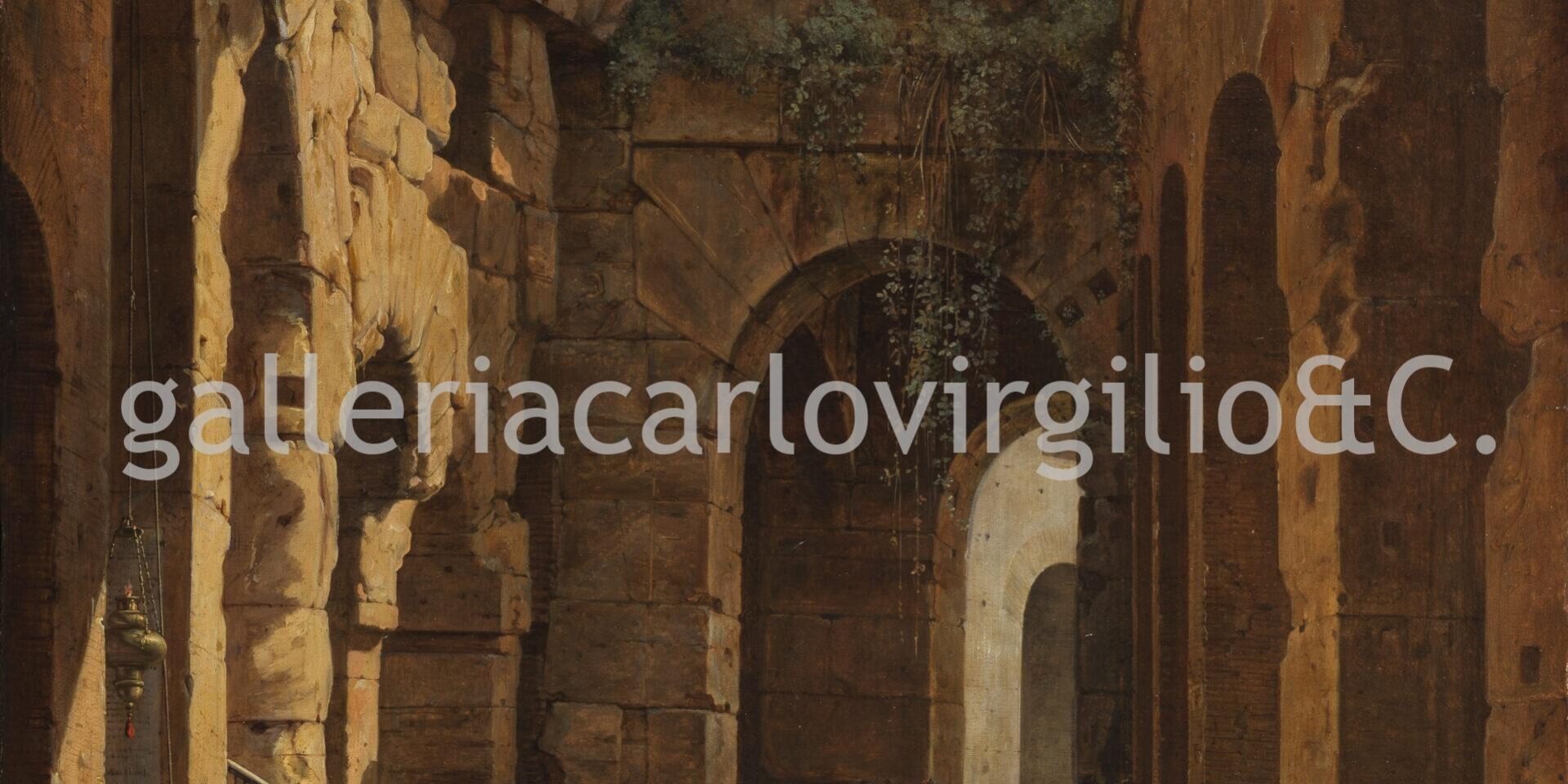

François-Marius Granet

Aix-en-Provence 1775 – 1849

Interno del Colosseo • 1802 ca.

oil on canvas, 99 x 75 cm

For so long, artists have celebrated the majestic beauty of the Colosseum, the Roman amphitheatre built in the time of Emperor Titus (79-81).

For so long, painted views have reflected the fascination for that grandiose elliptical structure, the imposing vaulted arches, three orders of loggias and solemn sequence of arcades.

Granet’s choice of composition is enchanting and inimitable, “early testimony of a romantic sensibility when Europe was still permeated by the rationality of the Enlightenment”, in the judgement of Marc Fumaroli, a great historian of French culture.

Perfectly conserved on the original canvas, the painting shows a partial view of the Colosseum as it appeared in the early years of the nineteenth century. Indeed Granet gives us the suggestive image of the amphitheatre before 1809, when the Napoleonic prefecture began excavating buried areas and demolished elements that had grown up over the centuries, and before Pope Pius VII (who returned to Rome in 1814 after being held prisoner by the French for almost five years) initiated a programme of restoration, integration and salvage destined to last two hundred years.

Hence the peculiarity of this scene is that it portrays the Colosseum before the archaeological “profanation” – as Granet described it – in other words before the intervention of the engineers and archaeologists eliminating forever the mysterious beauty of the ruin invaded by vegetation.

“The Colosseum struck me both for its architectonic shape and for the vegetation climbing over the ruins and producing an enchanting effect against the sky… There are wallflowers growing all over the place and acanthus with those beautiful serrated leaves, and honeysuckle and violets… There are shady arcades with patches of light so seductive that no painter could resist the desire to make a study of it” (Granet, Mémoires, 1872, ch. V).[1]

In this antiheroic view, far from the monumental stereotypes of the Colosseum, the artist captures the chromatic variations of a sight in a place not yet reclaimed by the archaeologists or stripped by weed killer.

Despite the ruin having been painted so many times, the artist establishes the charm through the originality of the angle, the erosion of shape through the light and a fluid and tonal brushstroke.

In our eyes, the image of the ancient and of Rome is perhaps not the same after meeting the minimal poetry of places such as Granet has revealed them.

His studies, drawings and paintings (in oil on paper and, more rarely, oil on canvas) cast aside framing the area from the outside. He set up his easel within, taking advantage of the spectacular frame of the arcades, the closeness of the ruins, and the symbiotic twist of architecture and nature; as he himself would recall years later on his brief return to the much loved city of Rome (1829): “I ran straight to the Forum and Colosseum; I greeted those marbles with sacrosanct respect, while reproving the men who have had the audacity to lay their profane hands on the beautiful stones that nature, with grace, had adorned with flowers and garlands, as though it wished to weave crowns for the architects and princes who erected them” (Granet, Mémoires, 1872).

As for his working method, Granet embraces the possibility of reproducing a sketch taken from life (Poplars Seen from an Arch of the Colosseum, Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet) within a much larger and more complex composition (Monks Among the Ruins of the Colosseum, New York, Roberta J. M. Olson Collection),[2] and of producing variations on a scenic layout, as in the case of this Colosseum Interior. Indeed the same view can be found on a smaller scale, in a less lyrical and more anecdotal canvas, where small figures have been included and the light effects altered (The Ruins of the Colosseum animated by People/Les ruines du Colisée animées de personnages[3]).

Historical and landscape painter, François-Marius Granet, “cet enfant gâté de la peinture”, was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1775. His is a story of social freedom – proletarian origins, third of seven children, father a master builder – marked by a close friendship with Count Auguste de Forbin (1777-1841), his patron, a wealthy lord from Provence, a traveller, a worldly individual and yet drawn to the mild, introvert Granet. It was Forbin who called Granet to Paris (1796), enabling him to study the Flemish and Dutch masters at the Louvre and obtaining admission to the highly sought after atelier of Jacques-Louis David, where in 1798 he managed to place his friend. A crucial sojourn – as it was for other landscape painters, from Simon Denis to Christoffer Wilhelm Eckerberg – for the long practice in simplification, conducted from life in front of the model, which is at the origin of the essential structure of Granet’s landscapes. He had a genuine vocation for colour that softened the structural rigour: “il sent la couleur”, said the prophetic David. This painting is proof of it, with its colourful and tactile stamp, a fragment carved from life, almost without design.

“All the artists who travelled to Rome talked about the city with such enthusiasm that I had a very great desire to go there” (Granet, Mémoires, 1872).

As a result, Granet too made his trip to Rome, entering by Piazza del Popolo in the summer of 1802. And Rome would be his city of choice for a sizeable part of his life, from 1802 to 1824.

The standing of Granet, history and landscape painter, also comes from him having lived parallel artistic lives and succeeding in two areas of painting, both of which owe their modern figurative composition to his talent.

Celebrated as the “peintre des capucins” and sought after by important patrons (Carolina Murat, Cardinal Joseph Fesch and Prince Francesco Borghese Aldobrandini) as well as esteemed by Ingres, Camuccini and Canova, Granet was the early interpreter of the desire for harmony and silence that followed the furore of the French Revolution. His monastery cloisters and silent church interiors – painted in Rome, Assisi and Subiaco – highlight rooted religiosity, in counter melody to the neo-medieval mysticism of Chateaubriand, who had published Génie du Christianisme in 1802. The measure of Granet’s success can be seen in Coro dei Cappuccini (Capuchin Choir), a painting of which the artist produced fourteen copies.

Equally, Granet held a prominent role in painting sur nature, more modern than Nicolas-Didier Boguet, bolder in his cuts than Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld, more rarefied and essential than Simon Denis, and more transgressive than Pierre-Athanase Chauvin.

Between Valenciennes and Corot, the artist positions himself as the leading figure of early plein air: for the ability to withdraw a visual fragment and give us ‘snapshots’ without posing time, for the romantic vein of melancholy expressed by Chateaubriand and for being so intensely a painter to shatter shape and colour.[4]

Anna Ottani Cavina

[1] Mémoires du peintre Granet, “Le Temps”, 28 septembre-27 octobre 1872, edited by L. Halévy, p, 11 (the handwritten manuscript, published posthumously, is conserved at the Musée Arbaud in Aix-en-Provence).

[2] A. Ottani Cavina, Paysages d’Italie, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Grand Palais 2001, p. XXXII, figs. 12, 13.

[3] The small canvas (41×33 cm) appeared at the Artcurial auction on 23 March 2022, lot 146.

[4] Granet’s role of protagonist at the origins of painting en plein air in Italy has been confirmed by a series of recent monograph exhibitions dedicated to him: Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet 1984; New York, Frick Collection 1988; Rome, American Academy 1996; Rome, Palazzo Altemps 2000; Paris, Grand Palais – Mantua, Palazzo Te 2001; Paris, Louvre 2006; Rome, Villa Medici 2009.

The Carlo Virgilio & C. Gallery searches for works by Granet François-Marius (1775-1849)

To buy or sell works by Granet François-Marius (1775-1849) or to request free estimates and evaluations

mail info@carlovirgilio.co.uk

whatsapp +39 3382427650